It was a bit of a surprise to everyone when Peter Daniell – later senior government broker for bonds and gilts – “went up” to Trinity College, Oxford.

The year was 1927 and he was a graduate of Eton (like his father and grandfather before him). The problem was that Peter was not, by his own admission, an especially strong student.

The Daniell family, unperturbed, reached out to a cousin who had been to Trinity. He relayed that he would “obviously, put in a word” and Peter duly got a place. Trinity proved to be a “wonderful” experience. While some Eton graduates “never knew anybody but Etonians the whole way through [their] Oxford careers”, Trinity was different. It recruited from a much wider range of elite private schools. Aside from the 10 Etonians, as Sir Peter recalled before his death in 2002, Trinity had “eight Rugbyans, eight Wykehamists, five from Marlborough [and] four from Tonbridge”.

Peter Daniell had a rich social life at Oxford. He received an allowance from his parents of about £300 a year (£15,500 in today’s money), which covered his expenses and allowed him to play golf and also join a dining club, the Gridiron, whose later members would include Boris Johnson, David Cameron and George Osborne. He didn’t recall exactly how he ended up joining because it all seemed rather casual (“Oh come on old boy, you must join the Grid”).

Despite having “a wonderful time”, however, he was “ashamed of my academic side at Oxford”. He “didn’t read very much”, his essays were “bloody awful” and he ended up with a “pretty ropey” third-class degree. Then again, as he explained, nobody really cared. The feeling was that “one probably would get a job” regardless.

And he was right. He moved seamlessly into a job at his father’s firm and was soon made a partner.

Sir Peter’s experience of Oxford in the inter-war period verges on the clichéd. But this does not mean it was unusual. In our new book, Born to Rule: The Making and Remaking of the British Elite, we draw on the 120-year database of Who’s Who and over 200 interviews with key decision-makers to chart the changing role that the universities of Oxford and Cambridge have played in incubating the British elite.

Our analysis shows that while reform and cultural change have eroded the sense of ease and certainty that “old boys” like Daniell once felt about their gilded passage into and through Oxbridge, both universities have remained remarkably resilient as the central switchboard of the British elite. There are some differences between the two universities; Oxford alumni are more often found in government and the media, while Cambridge alumni tend to go into science and medicine. But the proportion of them who end up in Who’s Who has remained high and largely stable over time.

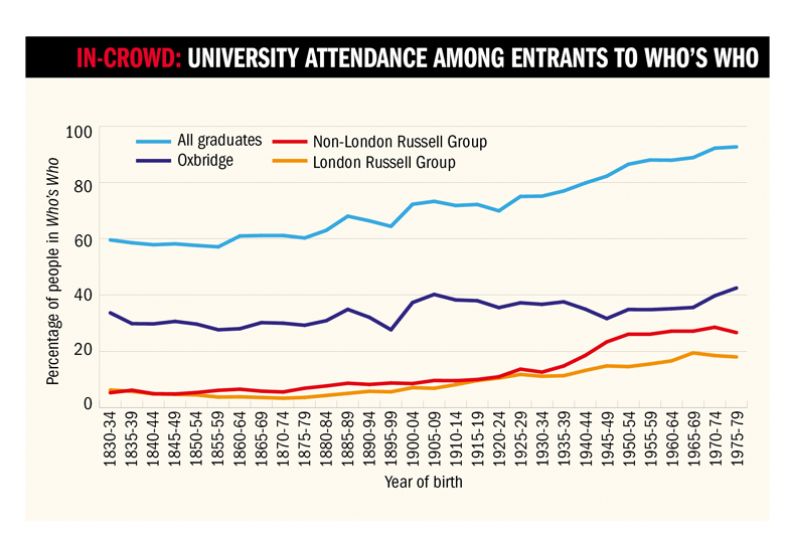

What is particularly striking about these figures is that the proportion of all university students attending Oxford and Cambridge fell dramatically during the same period. In 1861, there were around 3,400 university students in Great Britain and about 71 per cent of these students went to either Oxford or Cambridge. Today there are around 1.6 million full-time undergraduates and only 1.3 per cent of these are at Oxford or Cambridge. Yet even as the pool of competing graduates has mushroomed, Oxbridge has retained a remarkable stranglehold on elite recruitment.

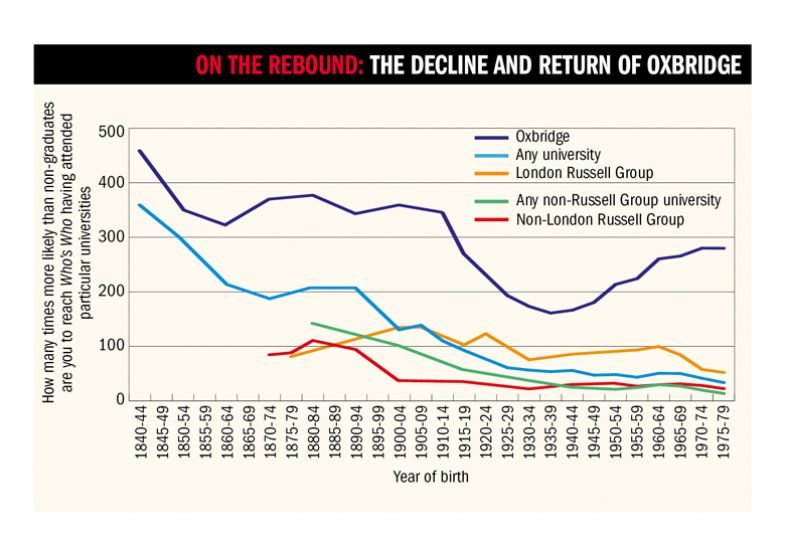

That said, the power of an Oxbridge education, relative to not going to university at all, has fluctuated over time. Throughout the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, Oxbridge graduates were somewhat ludicrously at least 350 times more likely to end up in an elite position than those who did not attend university. This was the Oxbridge that Peter Daniell entered in 1927, when entrance examinations were qualifying rather than competitive, admission was clearly influenced by school and family connections and academic performance once there mattered little. But this was about to change. Those born in the 1930s and early 1940s, entering Oxbridge in the mid-1950s and 1960s, faced a different reality as other universities started to emerge and Oxbridge’s grip on the elite weakened.

This had a profound impact on how the people we interviewed for this book spoke about their time at Oxford and Cambridge. Most clearly, we see a break between those born before the 1940s and those born after. Over one-third of interviewees born before 1940 spoke explicitly about performing badly, or not working much, while at Oxbridge. Only one interviewee born after 1940 said the same thing. What one hears between the lines in these later narratives is the end of certainty, the sense that an elite destination was no longer guaranteed.

But while the generation following Daniell’s, who approached Oxbridge with the same gentlemanly ethos of the past, may have found that their degrees were no longer a ticket to success, those that followed were quick to adapt – as were Oxford and Cambridge as institutions. This is manifested in the improved performance – presumably reflecting more rigorous admissions practices and a stronger student work ethic – of Oxbridge students in these decades. From the beginning of the 20th century up until the mid-1950s, the proportion of Oxford students receiving a third-class degree remained about 30 per cent. By the end of the 1980s, this had declined steadily to only 5 per cent.

This shift towards a more formalised academic meritocracy helps explain, at least to some extent, the revival of the fortunes of Oxbridge graduates in the second half of the 20th century. While Oxbridge graduates born in the early 1940s were just(!) 150 times more likely to make it into Who’s Who than those who never went to university, those born in the 1960s and 1970s were more than 250 times more likely to reach that directory of the British elite.

Yet a degree from Oxford or Cambridge is not a uniformly silver bullet. Our analysis shows that coming from a wealthy background or attending an elite private school has always accentuated the benefits of attending Oxbridge. In the 1980s, the journalist Toby Young explained the divide he witnessed at Oxford between “stains”, the hard-working, upwardly mobile children of professionals, and “socialites”, the alumni of schools like Eton and Westminster, who were either “rich, very upper-class, or both”, and our interviews echo this distinction.

Jagdish, an Indian-British lawyer from a lower-middle-class background, recalls the initial “culture shock” he experienced at Cambridge in the 1990s: “Because…it was…very public school-y…quite exclusive and quite cliquey…and I didn’t have that kind of natural confidence, which I think a lot of the public school applicants…had…And so, I kind of felt a bit overwhelmed.”

Alongside class-based forms of exclusion, there was, as Jagdish knew all too well, the question of race. Racism has historically been a big problem at Oxbridge. Indeed, Daniell’s Trinity College, Oxford had a particularly bad reputation; when the future chief minister of India’s Madras presidency, P. T. Rajan, applied in 1912, the college president, Herbert Blakiston, wrote to his headmaster: “We have not had an Indian at this college for nearly twenty years, and are not anxious to encourage Indian students to come.”

Racism structured the experience of many we interviewed, and it is striking that among Oxbridge alumni, whites are nearly twice as likely as graduates of colour to feature among the current British elite. Women have also been consistently less able to capitalise on their Oxbridge education than men. Among graduates of Oxford and Cambridge born at the beginning of the 20th century, men were four times more likely than women to reach elite positions. Among those born in the late 1970s, this gender gap has narrowed, but men are still 1.6 times more likely to have reached elite positions.

It may be too simplistic to say that there are only two Oxfords or two Cambridges. Yet this idea is still useful, we would argue, because it focuses attention on the fact that there has long been a social centre at these universities that has largely been occupied by young white men from very privileged backgrounds. This does not mean that these people all have an easy time or that they are guaranteed to get into the elite. Nor does it mean that these networks are entirely rigid. But it does suggest that the historical dominance of these groups has created a durable set of norms and practices at Oxbridge, often institutionalised via particular social clubs or societies, that contribute to the foundation of friendships that persist long after university and often provide tangible sources of social capital later in life.

Part of the charm of Oxford and Cambridge is their seeming imperviousness to change. But we would argue that they can and must be reformed to reflect the enduring role they play in the making of Britain’s elites.

In Born to Rule, we suggest two linked reforms aimed at changing who gets admitted. The first addresses the issue of who applies in the first place. Only 12 per cent of state school students in the north east of England who achieve three As or above in their A levels apply to Oxford or Cambridge. By contrast, for London, it is 43 per cent. These differences in application rates are a crucial component of geographical inequalities in the student body, as the admission rate of applicants from the north east is about the same as for London applicants.

To address this, we would advocate removing the applications process to Oxbridge entirely for academically able students and replacing it with a system in which both universities recruit by putting the best-performing 5 per cent of students from across the country into a lottery and then randomly selecting students from this group. The US state of Texas did something similar and it has opened up their flagship universities to underrepresented groups.

By itself, however, this reform would do little to break the dominance of private schools, whose alumni accounted for 27.4 per cent of Cambridge admissions in the 2023 cycle and 32.4 per cent of Oxford admissions (both rises on the previous year). We would propose, therefore, to restrict the proportion of domestic Oxbridge admissions accounted for by privately educated students to 10 per cent, which is the proportion of people in the UK that have attended a private school at some point in their education.

Indeed, it would make sense to apply that ceiling to the Russell Group universities more broadly; the impact on admissions would vary across institutions but would be especially large at Durham University, 38.6 per cent of whose admitted domestic students in 2023 were privately educated. Across Russell Group universities as a whole, the measure would reduce the proportion of privately educated students by around 50 per cent.

But why would we want to make it harder for what many perceive as the best schools to send their students to elite universities? In our book, we show that alumni of the Clarendon Schools – the nine-strong group of elite independent schools, including Eton, Rugby and Winchester – remain 52 times more likely to reach elite social positions than those attending other schools. Their stranglehold on elite recruitment, we believe, is perverse and makes a mockery of the idea that access to top positions in the UK is meritocratic.

Many of the British public agree. About 50 per cent think private schools “harm Britain” because “they reinforce privilege and social divisions, give children from better-off families an unfair advantage and undermine the state school system”, according to YouGov polling. And one of the reasons the UK cannot loosen the grip of these schools on elite positions is precisely because they are so successful at getting their alumni into elite universities. Introducing this limit in their propulsive power will not eradicate parents’ desire for private education, but it would probably dramatically quell demand and direct many parents back to the state sector.

This is obviously a radical move and would run up against significant resistance. One crucial objection might come from universities themselves. We know they care about widening participation but our proposal, they might object, would radically limit their autonomy to recruit the best and the brightest. The right of universities to choose their students has long been one of the key pillars of institutional autonomy – a right that remains an important component of the Higher Education and Research Act of 2017. But it is important to remember that the UK government often curtails institutional autonomy in the pursuit of socially valuable goals. Take the banning of discrimination based on gender and race, for example.

Besides, these reforms would actually do little to change who is taught at elite universities. In reality, it would amount to shuffling students with similar attainment levels between largely comparable institutions. Some of the private school students now attending Nottingham would go to well regarded non-Russell Group universities such as Essex, while some of the state school students at Essex would go to Nottingham. We are cautiously optimistic that Russell Group universities would not see a notable difference in “student quality”.

But even if the “quality” of admitted students declined, would this be a bad thing? It is undoubtedly thrilling to teach brilliant students, but universities are developmental institutions, places where students have their capacities expanded and improved. Reorganising admissions in this way would re-emphasise that transformative mission of elite universities.

Educational inequalities will not be removed entirely by either of our suggested reforms, of course. Affluent parents will continue to “buy” school quality when they purchase homes in expensive neighbourhoods. Our proposal might even intensify this process, and so there might be some need to complement these reforms with policies which stop residential sorting from crowding out low-income kids from good state schools. Despite this risk, we would maintain that there is also a broader symbolic value to our reforms, one which reinforces the intuition that the school you attended should not have a disproportionate impact on your life chances.

While their centrality may have waxed and waned over time, Oxford and Cambridge in particular remain key channels of elite formation. Under current rules, this distorts our higher education sector and continues to work in large part to reproduce class privilege. But the maintenance of the status quo is not inevitable. It is time for change.

Aaron Reeves and Sam Friedman are professors of sociology at the London School of Economics. Their new book, Born to Rule: The Making and Remaking of the British Elite, is published by Harvard University Press on 10 September.