In a move that has upset students, alumnae and faculty, Sweet Briar College announced earlier this month that it was changing its admissions policy and will no longer accept transgender applicants.

The small women’s college in rural Virginia has never had an admissions policy specifically for transgender students but has evaluated and admitted trans applicants on a case-by-case basis. The new policy holds that an applicant must confirm “that her sex assigned at birth is female and that she consistently lives and identifies as a woman,” according to Sweet Briar’s website.

Officials said they made the move to comply with recent changes to the Common Application, used by more than 1,000 higher ed institutions, which now lists four legal gender options. That change, Sweet Briar’s leaders said in a message to the campus community, “presents a challenge both for students applying for admission and administrators and staff making admissions decisions.”

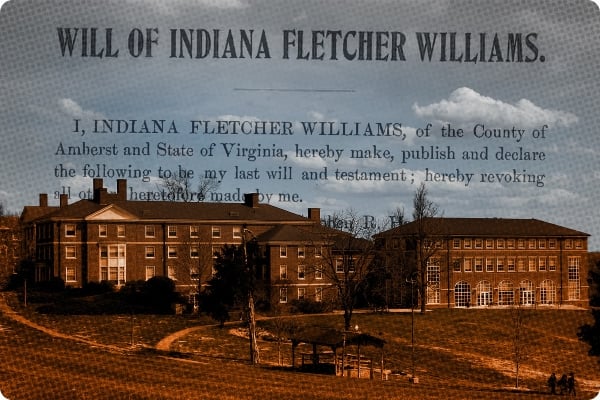

But key to the new admissions policy is how Sweet Briar views its own founding documents. The new transgender policy stems from the Board of Directors’ interpretation of the founder’s will, which emphasizes that the 123-year old college was established for the education of “girls and young women.” In a statement to the media, college officials noted that “political and other influences” have called “the meaning of the term ‘woman’ into question,” but the board “understands the term [women] in its historic and traditional way consistent with the intentions of our founder.”

In their email to the campus community, Sweet Briar leaders reiterated that the “girls and young women” phrase “must be interpreted as it was understood at the time the Will was written.”

Sweet Briar’s effort to honor the intent of its founders has led it to establish some of the most restrictive gender-based admissions policies among the 30 women’s colleges in the U.S.

The Language of the Will

Sweet Briar was founded in 1901 after the death of Indiana Fletcher Williams, who wrote in her will that the Sweet Briar Plantation she inherited from her father should go toward the creation of a women’s institute to honor the memory of her daughter Daisy Williams, who died at 16.

In accordance with Virginia law, the General Assembly codified the will, which established the nonprofit corporation that would carry out the dictates of Williams’s trust.

Those documents are the reason Sweet Briar remains open today, even after a prior board and president tried to shut it down in 2015 due to “insurmountable financial challenges.” But alumnae and others sued, arguing that college officials had no right to sell the property bequeathed in Williams’s will. After much legal wrangling—which culminated in the case reaching the Virginia Supreme Court—the alumnae prevailed, giving new life to Sweet Briar despite the mass exodus of students put off by the attempted closure. A whirlwind fundraising and recruiting effort helped to resuscitate the small college.

Now the same documents that kept Sweet Briar open continue to shape its future.

“As the founding document, the language of the will is the starting point for the college’s leadership in making decisions about the college and its mission,” Sweet Briar president Mary Pope Hutson told Inside Higher Ed. “In that document, it says the will imposes the requirement that the college be a place of learning for girls and young women.”

Hutson, a 1983 Sweet Briar graduate who was a key fundraiser before becoming president last year, said the board is bound to follow the will. And based on existing state case law, Sweet Briar leaders are required to consider how Williams viewed women and to honor that intent—even if current social norms do not reflect the founder’s perspective.

“The board cannot change the words or the interpretation of the will,” Hutson said. “I think that’s important.”

There has, however, been one major change to the administration of the will. Williams specified that Sweet Briar should be a college for white women—a stipulation that changed during the civil rights movement, when Sweet Briar sought to admit nonwhite students in compliance with recently established federal laws. College leaders requested permission from the state to do so in 1964 but were rebuffed, prompting a lengthy legal battle. The first Black student was eventually admitted in 1966 under a temporary order; the racial restriction was officially lifted by a court in 1967.

Reactions on Campus

As news of the revised policy spread on campus, students expressed disappointment.

Isabella Paul, a transgender and nonbinary student and president of Sweet Briar’s Student Government Association, said the move sparked widespread opposition on campus, with numerous organizations speaking out against it. Students were surprised by the change, which was made over the summer, Paul said, and by the administration’s failure to provide insight into their deliberations. Paul added that students plan to press the board to overturn the policy.

Numerous student groups took to social media to share their concerns.

“We do not agree with these terms and we will continue to support, grow, and advocate for the LGBTQIA community on Sweet Briar’s campus regardless of these new terms,” the Gay, Lesbian, or Whoever student group (GLOW) posted on social media, promising an event to discuss the changes.

Alumnae have also expressed outrage, challenging the decision on social media and encouraging the board to rethink the move. Some have threatened to withhold donations, a key source of revenue for SBC, which essentially fundraised its way back to life after the closure attempt.

Sweet Briar’s Faculty Senate issued a resolution on the new admissions policy on Monday night, urging the Board of Directors to reverse course. It argued that transgender students are “precisely the students who benefit from attending an institution that is historically dedicated to gender equity in a world where women were underserved and undervalued.”

John Gregory Brown, chair of the Faculty Senate, told Inside Higher Ed he found the new policy “morally repugnant” and bad for the college. He accused the board of adopting the change without consulting with faculty, alumnae or other members of the Sweet Briar community.

He also suggested “the originalist argument” used by the board was “ludicrous.”

The National Picture

Transgender student admissions policies vary across the nation’s 30 women’s colleges. Most offer some flexibility, often requiring that students simply identify and live as women, regardless of what appears on their birth certificate.

Maggie Nanney, a sociologist who has studied transgender admissions policies since 2013, said by email that most policies were adopted between 2015 to 2018, following the case of Calliope Wong, a transgender woman denied entry to Smith College “due to the fact that her gender identity in her application materials and her legal sex in her financial aid form were incongruent.”

Student protests followed, leading to policy changes at many women’s colleges.

“Broadly speaking, most women’s colleges (and approximately half of men’s colleges) have adopted an admissions policy for transgender students. These policies, however, vary widely in what they cover—for example, some policies only cover the time of admission, while others discuss matriculation and graduation,” Nanney wrote. “Some, like Mount Holyoke, are widely inclusive of a variety of identities, while most have settled on accepting students who identify as women at the time of admission (regardless of sex assigned at birth or legal documentation).”

Nanney believes the policy changes in recent years have been driven by “our evolving understanding of gender and the expanding availability of gender identities to describe our lived experiences.” She also credits the increased social media connectivity that allows students to communicate over shared issues, and “the evolving social-political climate around trans rights.”

And admission policies are still evolving with regard to gender.

Though both the College of St. Benedict, a women’s college, and St. John’s University, a men’s college, accepted transgender students as far back as 2016, the two Catholic institutions changed their respective admissions policies last year to welcome nonbinary students.

Others, such as Wellesley College, have faced pressure to admit transgender men.

Saint Mary’s College, a Catholic women’s college in Indiana, approved a decision to accept transgender applicants last year, only to immediately reverse the move amid sharp criticism.

Amid the fallout of Sweet Briar’s new admissions policy, Hutson said the college is listening to stakeholders, inviting comments and feedback during multiple meetings held on campus. But Hutson stressed that Sweet Briar is unlike its peer institutions in that it is bound by a guiding document that is more than 100 years old.

“None of the other women’s colleges are governed by a will and donor intent and a document that was actually codified into law in the [Virginia] General Assembly. We’re a category of one,” Hutson said.